With all the different scissors out there it can be confusing to a new sewer as to what is actually needed. Three basic scissors should be sufficient to make any garment. There are left-handed versions as well as the standard right. I suggest two different marking wheels to transfer pattern markings--one for wovens whose wheel is notched, one for knits in which the wheel is smooth.

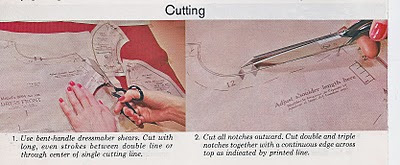

For cutting your fabric a 8 to 10 inch pair of bent-handeled dressmaker's shears will cover any job. Also a 5-6 inch pair of scissors can be best used to precision clip into curves and smaller areas. Pinking shears are used for finishing raw seam edges but one can forgo this pair if you have a serger or seam edge stitch on your sewing machine. Today, I often use a rotary cutter but such new-fangled items were not "invented" as of 1973.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Cutting straight lings: Open the shears wide and taking the fabric the entire length of the blade. Cut with one long steady closure for a smooth edge (No Snippy Choppy motions! Just smooth and efficient shear).

If there is a pattern piece that is difficult to access to cut correctly, cut around pattern, leaving margin of fabric so you can handle it and do a better job with cutting it without a problem. See Picture of sleeve above.

For Curves: open the scissors halfway and don't quite close them all the way while cutting to avoid jagged lines. Your goal is a smooth curve.

Right Angles: Cut along one line, then remove scissores and approach other line to the point where the lines meet. Do not swivel at the corners, you want a crisp true angle.

Clipping-- Use the 5 or 6 inch scissors and snip curves, small details and notches with the tips of the blades. Don't open them all the way so you have better control over the depth of the cut.

Pinking-- Open shears wide and close smoothly along the unfinished edges of the seam.

|

| click to enlarge. |

Marking: Utilize the marking wheels with the transfer paper. Run a saw-tooth wheel over the pattern markings (the transfer paper is layered with transfer medium down on top of wrong side of top fabric under pattern paper and a sheet facing up on the wrong side of the bottom fabric-- the pattern paper on top of all.-- See image A)

Here is an image of a dart marked on the fabric:

Thread Traced Marking

I would not necessarily mark the button placement until trying on the garment and placing them where they fit me the best.

Using Pins instead of tracing wheel and transfer paper: